[Previous entry: "Olympic Baseball - August 18, 2004"] [Main Index] [Next entry: "Phillies Journal - 2004"]

08/18/2004 Archived Entry: "Cooperstown Confidential"

Cooperstown Confidential, August 12, 2004 - Regular Season Edition

by Bruce Markusen

Helmets Head On

With John Olerud making recent headlines as the newest member of the New York Yankees, the rather esoteric subject of players wearing helmets in the field grabs hold of my slim-witted attention. Of all the current major leaguers, Olerud is the only one who wears a batting helmet at his position in the field, excluding those ever-endangered members of the catching fraternity. Olerud’s choice of headgear stems from a near tragic incident he endured during his college years; while attending Washington State University in 1989, Olerud suffered a brain hemorrhage and an aneurysm during a morning workout. Though he recovered, doctors advised him to wear a protective batting helmet while playing first base or pitching (he was a two-position player in college), in order to protect against line drives and collisions with baserunners that might result in contact with the skull.

By now it would probably be safe for Olerud to discard the helmet in favor of a soft cap, but matters of habit and superstition have compelled him to continue wearing the hard hat at all times throughout his professional career. While he is the lone active major leaguer to wear a helmet in the field, he is by no means the first to do so in the history of the game. It’s happened from time to time over the past 50 years, dating back to the first team that made full-temple helmets a permanent addition to their inventory of baseball equipment.

1953 Pirates: During the 1953 season, the Pittsburgh Pirates became the first team to permanently adopt batting helmets, taking the field wearing rather primitive fiberglass “miner’s caps” at the mandate of general manager Branch Rickey, who also owned stock in the company producing the helmets. Under Rickey’s orders, the Pirate players had to wear the helmets both at bat and in the field, which explains all of those old black-and-white photographs of 1950s Pirates like Toby Atwell, Bob Friend, and Nellie King wearing helmets in every pose and posture. Even manager Fred Haney joined the helmet-wearing brigade, apparently to protect himself from banging his head against the top of the dugout when making visits to the mound. The helmets became a permanent feature for Pirate hitters, but within a few weeks players began disavowing their use in the field, partly because of their awkwardly heavy feel and partly because of the remote possibility of a batted or thrown ball striking a fielder in the head. Once the Pirates discarded the helmets on defense, the trend disappeared from the game for nearly the next decade.

Felix Torres: An obscure infielder for the Los Angeles Angels during their early years, the Spanish-speaking Torres was probably best known for the curious way that he answered the phone, always greeting a caller with the words, “Hello baby.” More pertinent to this article, Torres ended the drought of helmets in the field when he started wearing one at third base during the 1962 season. Torres’ decision to sport a helmet might have been influenced by an incident he once witnessed in a minor league game. Playing for Class-D Douglas (Georgia), Torres and his mates stopped off for a series in a small town called Sandersville. During the game on enemy turf, one of his teammates, a pitcher named Willie DeJesus, started to warm up in the bullpen. Shortly after beginning his warm-up tosses, DeJesus heard some heckling from fans in the stands and responded with a few verbal retorts of own. The fans, not taking kindly to the unwanted response, began throwing bottles and cans at the relief pitcher. Torres, several of his teammates, and his manager came to the aid of DeJesus, eventually bringing the incident to an end.

Richie Allen: Helmets in the field started to become trendy when the Phillies’ star felt compelled to wear one in left field as a means of security against an unruly crowd. Often a verbal target of fans in Philadelphia, Allen one day found himself bombarded by hundred of pennies being thrown by fans in the left field stands at Connie Mack Stadium. The demonstration of violence convinced Allen to wear a helmet in the field for the rest of his career, whether playing in left field or at first base. Even after being traded away by Philadelphia, Scott continued the practice while playing in St. Louis, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Oakland. For awhile, Allen was the only major leaguer to use a helmet when fielding his position, an oddity that only added to his uniquely controversial persona.

George “Boomer” Scott: Like Allen, Scott began wearing a helmet in the field because of unruly fan reaction, but his decision came in response to actions of the road fans, not the hometown faithful at Fenway Park. Given his brush with such violent strains of fan anger, the Red Sox’ infielder decided to make the helmet a permanent addition to his baseball wardrobe. Looking awkward atop his large head and massive frame, the clunky helmet belied Scott’s fielding grace; “Boomer” won eight Gold Gloves for the Red Sox and the Brewers. Yes, soft hands and agile footwork overcome hard helmets at all times… On an unrelated side note, Scott also used to wear a distinctive necklace made of what appeared to be ivory tusks. When a reporter asked Scott exactly what the necklace consisted of, the oversized Boomer responded: “Second baseman’s teeth.”

Horace Clarke: I haven’t been able to figure out exactly why Clarke wore a helmet while patrolling second base for the Yankees; perhaps it had something to do with his fear of being upended on double-play takeout slides. (Column contributor Repoz asked former Yankee broadcaster Bob Gamere about the reasoning behind Clarke’s helmet; Gamere says it may have stemmed from a 1969 incident in which Clarke was hit in the head with a ball.) During his eight seasons in New York, Clarke received constant criticism from fans and media for his inability to turn the double play. Rather than attempting to pivot on double plays at the bag, Clarke often bailed out, jumping out of the way of runners while holding onto the baseball. Clarke, whose range to his right also left something to be desired, was so vilified in the Big Apple that fans once booed him during pre-game introductions on Opening Day and one writer repeatedly referred to him as “Horrible Horace.” That’s Horrible Horace with a helmet, please.

Joe Ferguson: Primarily a catcher during his major league career, Ferguson also played in right field from time to time. The time-sharing plan began early in his career with the Dodgers, who already had a fine defensive catcher in Steve Yeager but wanted to make room for the power-hitting Ferguson in their batting order. When the 200-pound Ferguson took to the outfield—a position that he hated to play—he made sure to take his hard hat with him. As with Clarke, I haven’t been able to pinpoint an exact reason, but it may have had something to do with a lack of confidence in catching the baseball. Ferguson once lost two fly balls in the sun during the same game, making his head an easy target for a ball dropping out of the sky. While Ferguson’s fielding prowess in right field sometimes made his managers nervous, he didn’t lack for ability in throwing the baseball. Playing for the Dodgers during the 1974 World Series, Ferguson unleashed a 290-foot throw from right field to the catcher, taking a potential run off the board for the Oakland A’s. Ferguson certainly didn’t lack confidence in his throwing, among other abilities. He once told a sportswriter, “I believe I can be a better catcher than Johnny Bench.” Well, it didn’t exactly turn out that way, but then again, Bench could never play the outfield quite like Fergie.

Dave Parker: One need look no further than the incident that took place on July 12, 1980, to find the motivation that “The Cobra” needed to start wearing a helmet in right field. During the first game of a doubleheader against the Dodgers at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, one particularly nasty hometown fan fired a nine-volt transistor battery at the beleaguered Parker, who had come under criticism for playing poorly while saddled with an injured knee. The battery barely missed Parker’s head, whizzing by his ear before landing on the artificial turf. Stunned by the near miss, Parker walked off the field and didn’t return for the rest of the doubleheader. Amazingly, the battery episode wasn’t the first time that Parker found himself in the line of fan fire. Earlier in the 1980 season, another idiotic fan had hurled a bag of nuts and bolts in Parker’s direction. Thankfully, the bag missed its target, as did the nine-volt battery.

How Not To Win Friends

J.P. Ricciardi may very well have been justified in firing Carlos Tosca last week, given the dreadful level of play to which the Blue Jays have sunk. Yet, Ricciardi is quickly adding to his reputation as an insensitive employer, one who lacks compassion in the way that he dismisses underlings and one who may be more interested in placing blame on others than accepting significant responsibility on his own part for the team’s failures. When Ricciardi first joined the Jays, he fired a host of longtime scouts whom he felt had lost touch with the ability to objectively analyze and project talent. Again, Ricciardi may have been justified in his decision, but the firings were so callous and sudden that it left a bad taste throughout baseball’s scouting community. Then Ricciardi decided to fire Tosca after a Sunday afternoon loss to the Yankees, thus denying Tosca the dignity of having a chance to meet with his team for a final time.

To make matters worse, Ricciardi couldn’t resist taking a subtle shot at another team’s manager in attempting to justify the Jays’ struggles and the reasoning behind the firing of Tosca. Trying to legitimize the team’s failings because of the organization’s emphasis on youth, Ricciardi offered this nugget to the press: “Obviously we’re not the Yankees. Joe Torre would probably have a hard time managing with our club because he’d get so frustrated with the young players.” So it wasn’t enough for Ricciardi to fire his own manager; he also had to take a shot at Torre, a certified future Hall of Famer, by insinuating that he doesn’t do well in handling younger players. That might come as news to players like Derek Jeter, Jorge Posada, Nick Johnson, Alfonso Soriano, Andy Pettitte, and Ramiro Mendoza, all of whom developed as young Yankees under the guidance of Torre and his coaching staff.

Card Corner

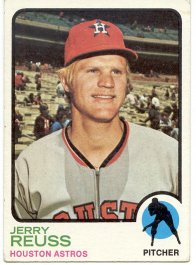

In honor of Jerry Reuss’ recent visit to the Hall of Fame, let’s put the underrated left-hander in the spotlight of this week’s Card Corner. During his stopover in Cooperstown (which is about an hour and a half from Binghamton, where Reuss serves as the pitching coach for the Class-AA Binghamton Mets), Reuss told an interesting story about a little-known incident that culminated in his trade from the St. Louis Cardinals to the Houston Astros. In 1972, Reuss reported to spring training wearing a mustache, something that just wasn’t done at the time. Little did Reuss know that his grooming decision would result in the end of his Cardinals’ career.

No one in St. Louis’ front office said anything to Reuss about the mustache, which seemed to be a non-issue, in stark contract to the ongoing soap opera with the Oakland A’s, where several A’s had grown spring mustaches. A 14-game winner in 1971, Reuss appeared set to take his place in the Cardinals’ rotation, right behind Hall of Famer Bob Gibson and the newly acquired Rick Wise (the compensation in the ill-fated Steve Carlton trade). Then, in the middle of spring training, the Cardinals announced another trade, this time with the Houston Astros. Much to his surprise, Reuss discovered that he was the principal figure headed to Houston. Reuss would never again appear in a Cardinal uniform.

For years, Reuss thought he had been traded because of his request for a salary increase in the spring of ‘72. It wasn’t until after his retirement that Reuss found out the true motivation behind the trade. Cardinals owner August “Gussie” Busch so hated Reuss’ mustache that he ordered general manager Bing Devine to trade him. Unlike A’s owner Charlie Finley, Gussie didn’t bother to deliver a second-hand message to Reuss, telling him that he had to shave the mustache or else. Deeming Reuss’ mustache some kind of baseball sin, Busch banished him to Texas without warning—or a second chance.

Not knowing that the mustache had ignited Busch’ temper, Reuss kept his facial hair intact in Houston, as evidenced by his 1973 Topps card. (The mustache is a little bit hard to spot because of Reuss’ blonde hair, but it’s there.) Reuss made his debut for the Astros on April 19, just four days after Reggie Jackson had made baseball history by unveiling his mustache—the first since Wally Schang in 1914—on Opening Day against the Minnesota Twins.

One other sidenote about Reuss’ 1973 card: take note of the zippered jersey the Astros used in the early 1970s. Several teams had tried the zippered look in the 1940s, only to discover that the zipper could inflict major damage on a player diving or sliding headfirst. The Astros, along with a few other teams in the seventies, apparently didn’t learn the appropriate lesson and gave the zipper a second chance, only to abandon it quickly.

Pastime Passings

Bob Murphy (Died on August 3 in West Palm Beach, Florida; age 79; lung cancer): Diagnosed with lung cancer earlier this year, Murphy had just concluded a long and distinguished career as a play-by-play broadcaster in 2003. One of the New York Mets’ original broadcasters in 1962, Murphy teamed with Lindsey Nelson and Ralph Kiner to form one of the most popular local broadcast teams of all time. The three men split up radio and TV duties for 17 years, before Nelson decided to leave New York for play-by-play duties with the San Francisco Giants. In 1982, Murphy was moved to radio broadcasts on a fulltime basis. Although Murphy considered the move a demotion of sorts, he truly shined in the radio booth, where the need for explicit descriptions of plays as they happened better fit his broadcasting style.

Murphy’s career in broadcasting spanned 50 years. He previously did play-by-play for the Boston Red Sox, with whom he began his major league career in 1954. Six years later, he moved on to do Baltimore Orioles broadcasts. In 1994, while still active as the Mets’ play-by-play man, he received the Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasting excellence, an annual award bestowed by the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In tribute to Murphy, the Mets will wear his name on their left sleeve for the balance of the 2004 season.

COMMENTARY: Bob Murphy was never that highly regarded or fully appreciated when he worked Mets TV broadcasts with Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson. Kiner, with his propensity for malaprops and down-home storytelling, and Nelson with his loud sportscoats and frenetically excitable on-air style, tended to dominate the broadcasts. And then in the early 1980s, the Mets decided to move Murphy over to the radio booth fulltime, and that’s where he really became the voice of the Mets. Some broadcasters are just better suited to radio, and Murphy really seemed to find his niche there, even though he initially considered it a demotion. Within a few years, Murphy’s brilliant work on the radio had resurrected his career. By the late eighties and early nineties, Murphy had developed a whole new following, and was no longer the overlooked third man in the booth. Then came the Frick Award, much deserved and perhaps overdue, in 1994.

Working at my first post-college position at WIBX Radio (which carried the Mets broadcasts at the time), I found one of the real pleasures of the job to be running Mets games and listening to the team of Murphy and Gary Thorne, and later the tandem of Murphy and Gary Cohen. Murphy did such an excellent job of both describing the play-by-play in full detail, while also keeping up with the pace of the action at the same time. You always understood the way a play developed with Murphy at the microphone. He never had to backtrack in describing a play; he almost always got it right the first time around.

One of the hidden aspects of Murphy’s broadcasting style was his sense of humor. He didn’t use it very often, saving it only for those moments he considered the most appropriate—while sometimes targeting himself as the butt of the jokes. One of Murphy’s funniest lines occurred during an interview he did with Billy Sample of MLB Radio last fall, just before his retirement. Sample asked him how he would like to be remembered. Offering a simple deadpan response, Murphy said, “Favorably.”

He will be.

Cooperstown Confidential author Bruce Markusen is co-host of “The Heart of the Order: Old School Baseball Talk,” which airs each Thursday at 12 noon Eastern time on MLB.com Radio. He is also the author of three books on baseball, including A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, Roberto Clemente: The Great One, and The Orlando Cepeda Story. A fourth book, Ted Williams: A Biography (Greenwood Press), is scheduled for release this fall. And for those interested in the realm of horror and vampires, Markusen’s new book, Haunted House of the Vampire, will be available in October. For more information, send an e-mail to bmark@telenet.net.