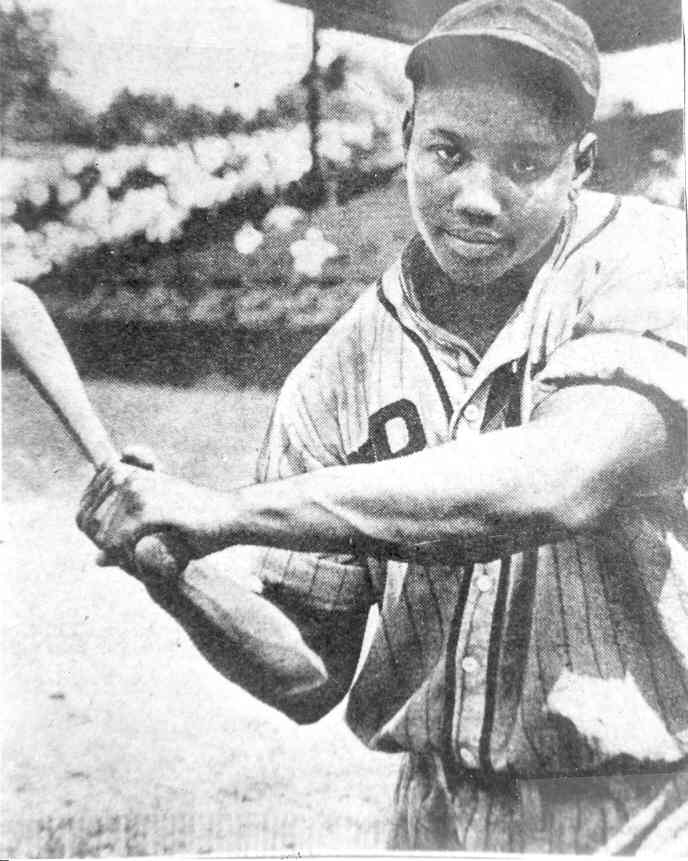

GIBSON'S STADIUM BLASTS

By John B Holway

Did Josh Hamilton

hit a ball over the bleachers and out of Yankee Stadium during the All Star

home run derby? For a breathless

second, it looked like it on the TV

screen.

Did Josh Hamilton

hit a ball over the bleachers and out of Yankee Stadium during the All Star

home run derby? For a breathless

second, it looked like it on the TV

screen.

Almost

78 years earlier an 18 year-old kid came within two feet of conquering the

House that Ruth Built, something that Ruth himself couldn't

conquer.

His

name was Josh Gibson.

_______________________________________

John

B Holway is author of

Josh

and Satch and

The

Complete Book of the Negro

Leagues.

Once

a name from the mists of baseball history, Gibson has now emerged from the

realm of legends, and we know a great many details of the man behind the

myth.

On

Saturday, July 27, 1930 Josh had been in the league only a few weeks when

he arrived in

There

were no monuments in the outfield then, of

course. Leftfield really was

“death valley.” The

bleachers stretched 481 feet away at their farthest point – it looked

like 481 miles to the right-handed

batters.

The

two runways between the grandstand and the bleachers were used as

bullpens. The bullpen gate in

left-center was 405 feet from home.

That's where Brooklyn’s Al Gionfriddo

robbed

Joe DiMaggio of a home run in the 1947 World Series – Joe never did

hit a homer in

A

weak earlier Josh had smashed a ball over the centerfield wall in

In

Before

the first game in

But

in the ninth Red came out of the game, and Broadway Connie Rector (he didn't

get his nickname by wearing blue jeans) went

in. A ten-year veteran, Rector

was

3-1

that season with a dangerously high 7.02 runs per

game – earned runs were not

compiled. But the year before,

he had been the best black hurler in the country with a

record

of 20-2. He wasn't

overpowering. He walked as many

men as he whiffed and completed only half his games, which was unusual for

that day. He pitched as hard

as he needed to. When

the slugging

Rector

threw the most tantalizing slow ball in

Rector

must have forgotten the clubhouse meeting, because he got one pitch a little

too close. Josh, with “those

arms like sledge hammers,” supplied all the power himself and sent the

ball whistling toward the bullpen like a golf

drive.

Rector

must have forgotten the clubhouse meeting, because he got one pitch a little

too close. Josh, with “those

arms like sledge hammers,” supplied all the power himself and sent the

ball whistling toward the bullpen like a golf

drive.

I

talked to three eye-witnesses, each one with different perspectives of the

blast.

Hall

of Famer William “Judy” Johnson was presumably in the visiting

Grays’ dugout. Mark Koenig,

the last survivor of the 1930 Yanks, said the home team sat behind third

base and the visitors behind first, just the opposite of the present

arrangement. Johnson, therefore,

would have had a good view of the drive to left (unless he was coaching at

third base). Anyway, he said

the ball “went out over the roof, over

everything.”

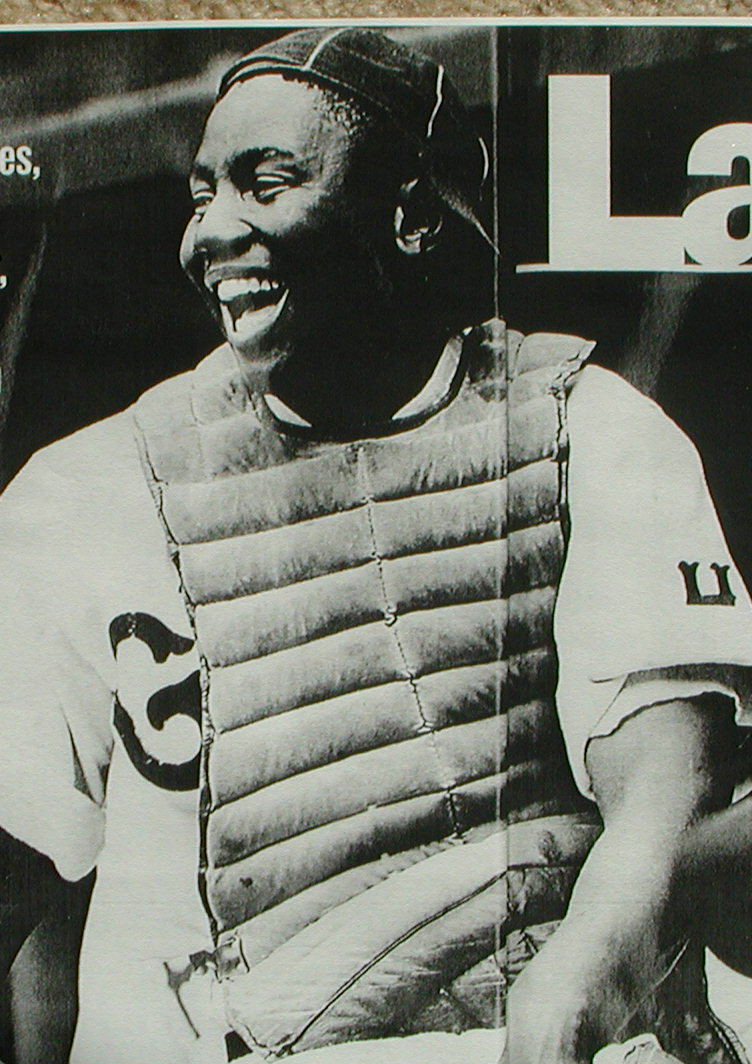

Brown,

the catcher, presumably had the best

view. He said the ball went

over the roof and hit the back of the bullpen, about two feet from the top

of the

wall.

How

far from home is the wall? Even

the Yankees’ public relations office couldn't tell

me. Using a scale diagram

circa 1950, the wall was, as close as I can measure it, 505 feet from home

(assuming that the plate

hasn't

moved).

The

newspapers are of no use. White

papers didn't cover the game;

black

papers merely called it a “long” home

run. Gibson’s hometown

Gibson

himself in 1938 told the

Courier,

“I hit the ball on a line into the bullpen in deep leftfield.”

Josh was known as a line-drive

hitter, so we can assume that the ball did not go over the roof, though it

might have gone over the corner of the upper

deck.

The

balls Josh Hamilton hit in the contest this summer were

suspect. I cannot believe they

were regulation major league balls.

By contrast, Gibson was batting against a cheaper

Several

years later Gibson hit another monster shot into the

bullpen. I have found no newspaper

that mentioned it. Jack Marshall

of the Chicago American Giants told author William Brashler he saw it during

a four-team double-header in 1934.

I talked to two other men who saw the shot,

Thomas

said the ball landed in the bullpen and bounced into the bleachers, 17 rows

up. I said, “Jesus

Christ! I ain't

never seen a ball hit like

that before!”

Clint’s

buddy, Clarence “Fats” Jenkins, had run over from

centerfield. “Neither did

I, Roomie,” he

whistled.

A

white fan caught the ball. “You want it?” he called to

them.

“We

said, ‘Yeah.’ He threw

it down. After the game we took

a cab to radio station WOR and Ed Sullivan

[Daily

News columnist and later

a top TV personality] and gave him the ball on the

radio. He gave us

$50. I don't know what happened

to the ball.”

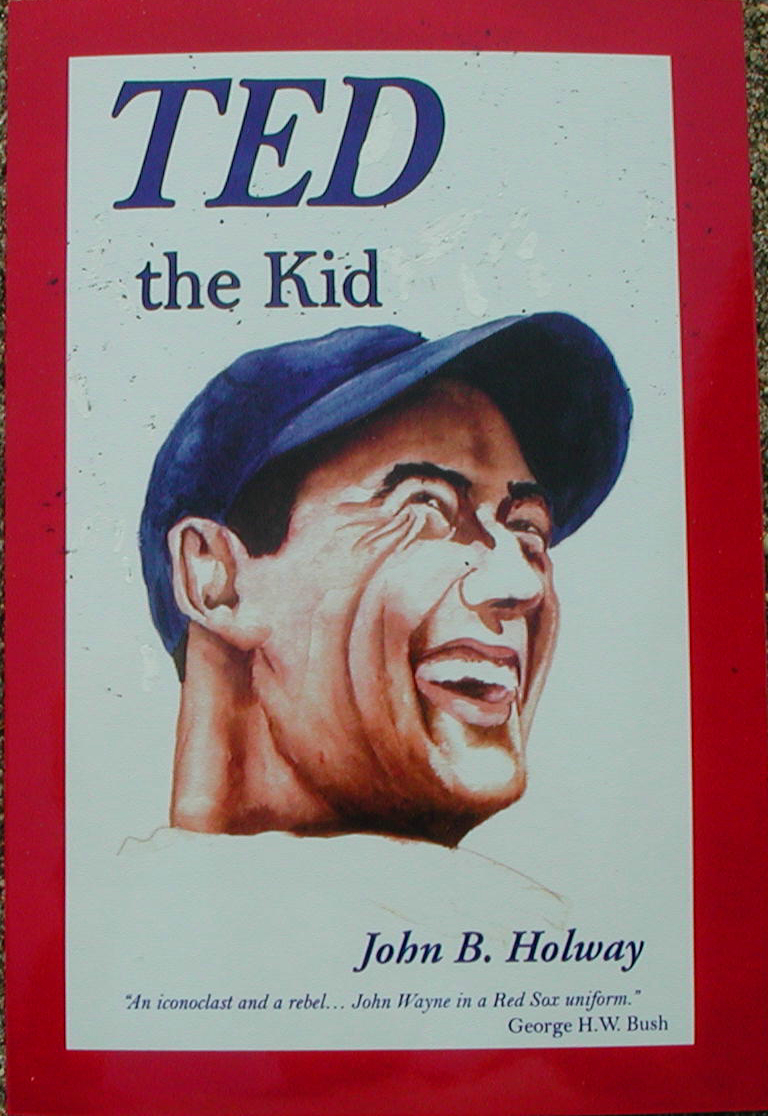

If you think you've read everything about Ted Williams,

think again. I knew him for

65

years since we were friends in high school, and I've never

read any book like this one.

Holway has new facts and statistics and pictures on almost every

page. He spent hours talking

to Ted and found out things Ted never told anyone

else. Most people don’t

know that he was half-Mexican or how his uncles taught him to play, and even

I didn't know that he called his shots on at least 17 home

runs. There’s a lot of

new stuff on his battles with the writers, his famous All Star Game home

run, Joe DiMaggio’s streak, and about Cobb, Sisler, Hornsby, and other

.400 hitters. This book really

brings the man and that era to life.

It’s a box seat ticket to

history.”

Bob

Breitbart, director, San Diego Hall of

Champions.

If you think you've read everything about Ted Williams,

think again. I knew him for

65

years since we were friends in high school, and I've never

read any book like this one.

Holway has new facts and statistics and pictures on almost every

page. He spent hours talking

to Ted and found out things Ted never told anyone

else. Most people don’t

know that he was half-Mexican or how his uncles taught him to play, and even

I didn't know that he called his shots on at least 17 home

runs. There’s a lot of

new stuff on his battles with the writers, his famous All Star Game home

run, Joe DiMaggio’s streak, and about Cobb, Sisler, Hornsby, and other

.400 hitters. This book really

brings the man and that era to life.

It’s a box seat ticket to

history.”

Bob

Breitbart, director, San Diego Hall of

Champions.

“Well done. There were plenty of people who racked Ted up and wanted to bring out the bad in the guy. He had a lot of pressure on him, but he was a really compassionate guy. Holway has told it like it is.” Bobby Doerr, Hall of Fame, Red Sox 1938-50.

“The

ballplayers all loved Ted. He

was a great hitter, a great human being, and a great

friend. Holway’s book captures

the spirit of those years –

absolutely. Reading it is like

being there in person. Every

serious baseball fan should have it in his library or on his coffee

table.”

Bob

Feller, Hall of Fame, Indians,

1936-56.

“Holway is the John Wayne of the keyboards.” John Thorn, editor, “Total Baseball.”

About

The

Last 400

Hitter(1001)

“Holway’s accounting of

the miraculous 1941 season is a joy to

read. Thoroughly researched

and carefully detailed, it is an affectionate tribute to a ballplayer, a

season, and an era.”

“Holway’s accounting of

the miraculous 1941 season is a joy to

read. Thoroughly researched

and carefully detailed, it is an affectionate tribute to a ballplayer, a

season, and an era.”

“I

entered baseball at just about the same time Ted did, so it was great fun

reading about Ted’s life, and it brought back many

memories. John B Holway has

skillfully revived a remarkable period in baseball history, as well as the

turbulent world surrounding it. I

thoroughly enjoyed reliving those times through this delightful

book.”

Jean

Yawkey, former Red Sox chairman of the board.

$35 + $4

s&h,

soft cover. Scorpio

Books,

18 new stories, many new pictures, and exclusive never-before published statistics span more than a century of history and bring to life an era that will never return.

Ted Williams recalled that in his rookie year of 1939, at each city the veterans pointed out, “Josh Gibson hit one there…. That's where Josh Gibson hit one.” “Well,” said Ted, “nobody in our league hit ‘em any farther than that.”

Read about:

Doc

Sykes, who hurled a no-hitter, out-raced KKK night-riders, and

watched a cross being burned on his

lawn.

Laymon Yokely, who whiffed Jimmie Foxx and Hack Wilson; Hack handed him his bat, saying, “Here, you take it, it’s no use to me.”

Frank Duncan, who started a riot and later sent Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers..

Connie Johnson, who reached the majors and tells of dueling Williams at the plate.

Piper Davis, who dazzled Globe Trotter fans and taught a teen-age rookie to get back up after a beaning.

“You taught me to survive,” Willie Mays told him. “You were the pioneers, you made it possible for us.”

“Blackball Tales, Holway’s third series of oral compilations relates the joys, travails, and aspirations of members of the Negro Leagues. Holway has done as much as anyone to chronicle the story of segregated baseball. Highly recommended for general libraries.” Library Journal.

$30 + $4 s&h softcover

Save $8. Buy both books for $65, and we pay the s&h