![]() Wartime

Service Adjustments

Wartime

Service Adjustments

![]() Salute to

a Hero

Salute to

a Hero

Whoa there! -

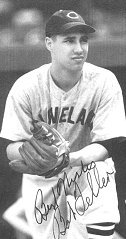

STRASBURG – THE NEXT FELLER?

At the age of 21 Stephen Strasburg won his first major league game, with 14 strike outs, and is already being compared to Bobby Feller.

Just a minute there.

In Bob’s first

game against big league batters, shortstop Leo Durocher had to be dragged

away from the water cooler and pushed up to the plate. Leo was only half-joking.

Bobby whiffed eight men in three

innings.

In Bob’s first

game against big league batters, shortstop Leo Durocher had to be dragged

away from the water cooler and pushed up to the plate. Leo was only half-joking.

Bobby whiffed eight men in three

innings.

In his first league start, he mowed down 15. Two weeks later it was 17, breaking the American League record.

And he was only 17 years old!

(He’s the only man in history to have as many strikeouts as birthday candles.)

As Washington manager Bucky Harris used to tell his players: “Go up and hit what you see. If you don't see it, come on back.”

Before Bob was Strasburg’s age, he had already won 55 major league games.

Age Wins Strikeouts

17 5 76

18 9 150

19 17 240

20 24 246

__ ___

55 712

Strasburg’s target:

21 27 261

At 22, Feller won 25 and whiffed 260.

John B Holway is author of The Pitcher, with John Thorn; Voices From the Great Black Baseball League and many other books and articles.

He spent the next four years in the Navy, shooting down Japanese planes from

the deck of a warship.

So if one compares Strasburg and Feller, age for age, then nothing Strasburg does from 2011 through 2014 should count. In fact, it will be interesting to see how Strasburg does and fantasize what Bob might have achieved at the same ages.

When Feller got back to full-time pitching in 1946, he whiffed 348 men, giving a hint of what he could have done in the almost four big missing years.

Fans can argue who was the fastest - Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Feller,

Sandy Koufax, Ryan, Randy Johnson, or Strasburg. In 1947 a radar gun timed

Bob at 107.

And Feller weighed only 185 – he'd be the smallest man on the

roster today. Imagine him on steroids!

Strasberg weighs 215-220. Pound for pound, he should be

throwing the ball 124 to 127

mph.

Here’s another stat:

Strasburg signed for over $15 million. Feller received a bonus of one dollar and a signed baseball. “I was happy,” he said, “all I wanted was a chance.” (Bobby was also grateful. When the commissioner declared him a free agent on a contract technicality, he received offers up to $200,000 but re-signed with Cleveland.)

Bobby drove his roommate, Roy Hughes, crazy practicing late into the night. Wearing an old-fashioned pullover nightshirt, Bob threw pitch after pitch into the pillow – Plop! Plop! Plop! “I couldn’t hardly sleep,” Roy groused.

Then Bob went home to Van Meter Iowa (population 300) on the Raccoon river, to finish the 11th grade. He grew up on a farm there and said milking cows had strengthened his arm.

His “high hard one” sailed right at the hitter’s fists and not far from his chin.

Feller pitched in an era when

hitters didn’t swing from the knob. Now even the littlest hitters swing

for home runs, happily trading strikeouts for homers.

Back then the American League

averaged seven strikeouts per game – for both teams. Today it’s

13. Pitching under 1930s conditions, Nolan Ryan’s record of 383 in one

year would be closer to 190.

“They have so many bushers

today,” Bob says. “And home runs, that's where the money is.

There’s no money in not striking out. They used to put the ball in play

after two strikes. But you have a better chance of a home run with three

swings than two.”

Does that mean that if Bob

had come along in this decade, he would strike out 700 batters a

year?

“Not 700,” he

admits. “But

‘more.’”

Like Strasburg, Feller had

a dazzling curve to go with his heat.

“It looked like it hit a rock and took a big bounce,”

A's infielder Dario Lodigiani marveled.

If Bob didn't have such a reputation as a flame-thrower, Ted Williams wrote, he'd have been famous as one of the game’s greatest curve ballers. He was “undoubtedly the premier pitcher of my era”

Joe DiMaggio agreed. “Feller is the best pitcher living. His curve ball isn't human. And I don’t think anyone is ever going to throw the ball faster than he does.”

In my opinion Bob was one of the top three or four hurlers of all time. Today’s fans hardly know his name, but he was the Nolan Ryan, Roger Clemens, or Randy Johnson of his day.

He ended with 266 wins. Without a war, it would surely have been 366

and probably 376, because they were the ‘mountain top” years of

most pitchers’ careers. Most great hurlers were 10% better in Bob’s

missing seasons – 23 thru 26 - than in the shoulder years before and

after.

In Bob’s missing seasons:

Walter Johnson won 30 games twice and a total of

149.

Christy Mathewson won 30 three times and 120 in

all.

At 24 Denny McLain won 30 games.

At 26 Ryan set the strikeout record, and Don Larsen pitched his perfect

Series game.

What could Bob have done?

“We'll never know, will we?” he shrugs.

It was a travesty when Feller was left off the 1999 All-Century team.

Bob Gibson (251 wins) and Sandy Koufax (165) made it. But not

Feller.

After school finished in June ’37, Bob went back to the Indians.

His picture made the cover of Time.

He was raised to $17,500 and bought a new Buick ($960).

In 1938, now a veteran of 19, Bob

missed a no-hitter when the first baseman was late covering the

bag.

In

the last game of the season, he faced Hank Greenberg, who needed two more

homers to tie Babe Ruth’s record of

60. It was dark, Hank wrote,

“and Bob really burned ‘em in.”

In

the last game of the season, he faced Hank Greenberg, who needed two more

homers to tie Babe Ruth’s record of

60. It was dark, Hank wrote,

“and Bob really burned ‘em in.”

“He couldn't hit me with an

ironing board,” Feller smiles today. “I gave him fastballs, side-arm

curves, a lot of sliders. I never changed up on him.” Bob whiffed Hank

twice, ending his home run hopes.

Bob struck out 18 men that day, a

new major league record.

That year he fanned a league-leading

240 – and walked 208, which is still the major league record. Like

the young Ryan, Feller often led the league in walks – it helped to

keep the hitters

loose.

Bob pitched three no-hitters. Without a war how would probably have notched one or two more. He doesn't disagree. “How many one-hitters did I have?” The answer is 12. And many of those were bang-bang plays or fielders’ lapses.

And Bob was a workhorse. In ’46 he pitched 371 innings, still the all-time record. Randy Johnson’s best was 270. Feller completed 31 games in 1940, Johnson’s top was eight.

They didn't count pitches then –

hurlers were expected to go nine innings every fourth day. Feller scoffed

at warnings that he was over-worked. How much rest did he need? “Three

days is good, two is OK.” That golden arm was actually gold-plated

steel.

Back then, a starter was expected to go nine innings every fourth day and pitch relief in between starts. Bob saved 21 games in his career; Ryan three, Johnson two.

I remember Bob clearly. He held the ball in the small of his back

and leaned forward to get the catcher’s sign, his glove slowly swaying

in front of his left knee.

After Bob got his sign, he

might step off the mound, hitch up his trousers, and walk back to the resin

bag to let the batter worry a little longer. He bent over and hefted the

bag a couple times. Then he stood gazing into the stands while rubbing the

ball. At last he stepped on the mound again. At this point the batter stepped

out. Like two sumo

wrestlers

playing

mind games, the dance went on between

pitches.

That little ritual isn’t

allowed today, but games last almost an hour longer

anyway.

At last a nod, knee up, half-turn

toward third base, turn back to the quaking batter - and

fire.

“Man, he’d

blind you,” whistled Negro

Leaguer Othello (Chico) Renfroe. “Can you imagine him having that delivery

– and he was

wild?”

In 1940 on a blustery Opening Day in Chicago, Feller was working on a no-hitter. He came down to the ninth, hanging on to a 1-0 lead with two out and the pesky Luke Appling up. Luke (.348 that year) could foul off pitches all day – he once fouled off 18 in a row – and the fast-balling Feller was tiring; he didn't want to throw 18 pitches to Luke. So with a 2-2 count, Bob took care of that problem by throwing two more wide ones (“an intentional walk,” Bob winks, “but nobody else knew it”).

That brought up Taffy Wright, who batted .337 that year but hit .444 against Feller. Bob reared back and Taffy smacked a ground ball to rookie Ray Mack at second. Mack juggled it, recovered, and just nipped Wright for the only Opening Day no-hitter in big league history.

That season Feller gave up an opposition batting average of only

.203.

In ‘41 Feller received about $35,000. The highest-paid players

were MVP Greenberg at $40,000 and Negro Leaguer Satchel Paige, reputedly

the same. DiMaggio (who was

about to hit in 56 straight games) also earned $35,000, and young Williams

(who would bat .406) got half as much.

Bob began an annual practice of helping a student through college with a

stipend of $105 a year, big money in those

days.

He won 25 games, and they did not come easy. Six

were shut outs, four others were by 2-1 scores.

With war imminent, Feller was deferred in the army draft because his father was dying of cancer and he was the sole support of his family, but he wouldn't ask for a 60-day deferment to finish the season. “I want to serve,” he said; “I think every young fellow should.”

This was the fifth no-hitter he had missed. It would be almost four years before he would win another game.

Bob

was driving across the Missippi

river to sign a new contract when he heard the news of Pearl Harbor. He told

Indians president Cy Slapickna that he was going to sign up the next day.

Bob

was driving across the Missippi

river to sign a new contract when he heard the news of Pearl Harbor. He told

Indians president Cy Slapickna that he was going to sign up the next day.

“You're kidding,” Cy

said.

“No, I'm

not.”

Bob took his oath from

ex-heavyweight champ Gene Tunney, head of Navy physical fitness. He traded

his Cleveland salary for $900 a year.

Bob was given shore

duty, teaching calisthenics. He demanded sea duty and was put on a ship

patrolling quiet waters in the Atlantic. Then he demanded

combat.

July 19 1945. Off Saipan Island in the South Pacific, Feller was chief of an anti-aircraft gun crew, blasting away at a sky-full of Japanese planes diving on his ship and the carriers it was protecting.

“I saw four dots above the horizon,” He told author Todd Anton. Were they American? “I blinked hard and rubbed my eyes. Nope. These were Japanese. We sent up a wall of white hot metal to meet them. I kept my four guns blazing – eight rounds per second.” The sky was alternately black with smoke, then bright from tracer bullets. Two attackers disintegrated in the air.

“Then a blot as big as a hurricane” showed up on radar, coming toward the task force. The horizon darkened “like a swarm of killer bees.” Torpedo bombers and dive bombers dove out of the sun, but Feller was wearing special goggles that let him pick out the enemy. “Two made it through, and a 250-pound bomb landed on our sister ship. The rest broke off the fight.”

An hour later another

wave of over 400 planes attacked. Only 35 got back.

“It was the most exciting 13 hours of my

life. But when the sun went

down, the Japanese naval air force didn't exist any more.”

An hour later another

wave of over 400 planes attacked. Only 35 got back.

“It was the most exciting 13 hours of my

life. But when the sun went

down, the Japanese naval air force didn't exist any more.”

Bob didn't even mention it in his biography! He insisted that “I wasn't a hero. The heroes didn't come back.”

But after that, “the dangers of Yankee Stadium seemed trivial.”

Did he regret losing those four years? No, he says firmly. “I made a lot of mistakes in my life. That’s not one of them.”

In 1946 Cleveland sent him a contract for $50,000. Then the Mexican League dropped a bombshell, offering Williams, DiMaggio, and Feller $120,000 a year each for three years, all the money up front.

They all said no. Bob signed the Cleveland contract, but with incentives, endorsements, a book deal, and barnstorming, he cleared $100,000 for the year.

Could he come back?

Bob answered the question April 30 in New York. Going into the ninth, he had a no-hitter and was leading 1-0. Snuffy Stirnweiss (.257) hit an easy ball to first, but Les Fleming bobbled it. The public address announcer broke all precedents by informing the fans that it was an error (they wouldn't do that even during DiMaggio’s hitting streak). The next day, Bob says, they installed a hit/error sign on the scoreboard.

Murderers’ Row was coming up -- Tom Henrich (.251), DiMaggio (.290), and Charlie Keller (.275). Tom sacrificed. Bob got two quick strikes on Joe as the fans screamed and clapped. Joe grounded out, sending the tying run to third, “so I had other things to worry about beside the no-hitter.”

The whole crowd was standing, rooting for Bob. The count on Keller

went to 3-2, and “I gave him my best overhand fastball.” As Stirnweiss

dashed home, Charlie swung. Mack charged the ball, slipped, and went down

on one knee, but he recovered and just nipped Keller. A roar of congratulations

erupted.

The whole crowd was standing, rooting for Bob. The count on Keller

went to 3-2, and “I gave him my best overhand fastball.” As Stirnweiss

dashed home, Charlie swung. Mack charged the ball, slipped, and went down

on one knee, but he recovered and just nipped Keller. A roar of congratulations

erupted.

It was the first no-hitter against the Yanks since 1919 and the first ever against them in Yankee Stadium. New York hit only two balls out of the infield. Bob considered this one his masterpiece.

Feller won 26 games and lost 15, including another 1-0 game. Bob should have won half of those 15, Ted thought, which would have given him over 30 victories.

Feller was also shooting for Rube Waddell’s strikeout record of 342. The hitters shortened their swings and punched the ball to avoid striking out, but in the final week, Bob pitched every other day and ended with 348.

But wait. A few days later someone corrected Rube’s total to 349 - no record for Bob, after all. Could he have reached 350 if he had known? He thinks so, but Hall of Fame researcher Gabe Schechter doesn't: He was so exhausted he didn't have another strikeout left in his arm.

That year Jackie Robinson joined Montreal, and Feller got himself in deep trouble when he opined that Jack would never make a major league hitter. Some critics still brand him a racist. I think that’s unfair – can't a guy express an opinion? Bob had been barnstorming against blacks every October since 1937. In 1945 he held Robinson to 0-for-4.

“Jackie was touchy, Bob says. “He was not the best Negro League player - Monte Irvin was, but Monte was injured. Jackie was very fast, but he was an average second baseman, and he was not a good high fastball hitter. The Yankees had all those high fastball pitchers, and he never hit them at all.” (Jackie’s World Series averages included .188, .182, and .174.) “He was a curve ball hitter.”

After the season, Bob organized a barnstorming tour against Satchel Paige’s black all stars, a chance for all the players, black and white, to make up some of the money they had lost during the war. The tour also show-cased some of the country’s best black talent and may have helped open doors to more blacks after Jackie.

Feller recruited two all-star teams and paid them $1700-6,000 a man. The Red Sox’s World Series share was $2,000.

Feller retired at age 35. Without a war, he might have been 24 wins shy of 400. “With the right team,” he told me once, “I would have stayed in another three or four years and gone for it.”

Now 91 with thick white hair, Bob makes public appearances for the Indians, spinning stories in a strong bass voice.

How good is Stephen Strasburg?

“Call me back,” he says, “when he wins his 100th game.”